FASHION

Fashion Faux Pas: Surprising Trend Challenging Clothing Injunctions

Céline Cabourg - Madame Figaro

30-November-2023

Shoes that stand out in an outfit... the fashion faux pas is gaining momentum and becoming a mode of transgression. Claiming one's difference, that's the spirit!

The epidemic began before summer. As temperatures started to rise, we encountered cohorts of girls in skirts and cowboy santiags, others in Bermuda shorts and pointed ballet flats. Even their boyfriends started wearing Birkenstock clogs with their sportswear outfits, an accessory of the 'daronnes bobos'. We realized that the feet were speaking. It resonated with this image of Lily-Rose Depp in the latest Coco Neige campaign, in a shimmering tight-fitting jumpsuit, wearing fluffy yeti boots.

On TikTok, where many fashion trends are born today, this viral phenomenon has been dubbed 'the wrong shoe theory,' a theory of the wrong shoe popularized by an until now unknown American stylist, Allison Bornstein. With more than 222,000 followers on the short video app, she has become the arbiter of new elegances. Be careful of translation pitfalls. The wrong shoe isn't ugly but rather incongruous, surprising, strange. It catches the eye and breaks up an overly perfect, smooth silhouette, shaking up a meticulously put-together look. It's the touch of boldness that disrupts the too well-coordinated ensemble. In this digital world saturated with images, difference has to be earned. Perhaps it even needs to be built more. This is what the inspirer of said theory explains: 'Because there is intention and choice, it gives a certain personality.

Before it went viral, the quirky shoe has always been the playground for many fashion designers who, first and foremost, drew attention to the tips of their toes. We think of pencil skirts paired with heavy boots by Miuccia Prada, but also Margiela's Tabi and Marc Jacobs' Kiki Boots, these 16-centimeter heel platform boots, whose copies this winter are worn by those who can't afford the original. However, the detail that kills, or saves, is not always a shoe, as shown by Élisabeth Quin and François Armanet in their book documenting one hundred and fifty years of fashion history, from Proust to Rihanna.

Sinatra's Trilby hat, Louise Bourgeois' black goat hair fur, Simone de Beauvoir's tie, each wardrobe piece can carry a symbolic function and signature. The authors provide a definition in the introduction: 'If the charming flaw, according to Stendhal, crystallizes desire, the "killer detail" is the arbiter of elegance. A signal that catches the eye, underlines an attitude, sublimates a style.' For François Armanet, the entire history of fashion is spiced up by these quirks: 'There have always been spikes of fancy defining a style. It can be a certain grace bordering on a taste fault, small arrangements to stand out from the classical cannons. I remember a discussion with Charlotte Gainsbourg, who, when asked "what is your beauty ideal?", had answered: "The bearing of a dancer and a torn stocking.”

Historical Precedents

Regarding shoes, specifically, the author of 'The Killer Detail' cites the example of Terence Stamp, the terrible dandy of Swinging London, perfectly dressed in velvet trousers and jacket, wearing a pair of electric blue Crocs. By doing so, 'he thus displays that he can afford anything, including combining this aristocratic chic with a pair of Croslite clogs, a thermoformable, antibacterial, and sweat-resistant material. With this touch of eccentricity, he also shows that he is not without humor and irony.' To gauge the audacity of the one who dares, it must always be placed in the context of the era. Thus, continues François Armanet, Brigitte Bardot, by adapting the ballet flat for city wear in the Saint-Tropez of the 1960s, invents the wrong shoe theory before its time: “A former petit rat of the Opera, she liked being barefoot, for existentialism and for the sensuality it provided. At the moment she does it, it's incongruous because she's the first.”

A Customized World

The specificity of the current context is well analyzed by Vincent Cocquebert in his latest book, 'Unique in the World. From Self-Invention to the End of the Other'. Our wrong shoe would be one of the symptoms of this withdrawal into ourselves, characteristic of the era he describes as 'egocentric': we no longer define ourselves by collective values, but by an individual utopia. 'This ties in with the theory of small differences,' he explains. Distinction is made through small artifacts, in a dynamic of mass customization. This results in a tension between us and the world we want to shape to our measure: we are inscribed in a system of mass consumption and try to extract ourselves from it by drawing on a toolbox of personal tricks. In this universe of what he calls depopulated microworlds, the other no longer really exists, “otherness is less and less so, but it becomes an audience.”

Accessories, Essential in Politics

Politicians, keen to convey messages and capture attention, have used this technique of stepping aside. Everyone remembers Roselyne Bachelot in 2008, then Minister of Health, Youth and Sports, coming out of a council of ministers at the Élysée in pink Crocs. It was fleeting, the time of a bet. To break away from what he calls the 'playmobilization' of communication, from these taps of lukewarm water continuously pouring out LinkedIn posts, Gaspard Gantzer, former advisor to François Hollande, says this to the private clients of his agency: 'Be aware of your flaws and cultivate them. If you have a little quirk, a lisp, a very particular vocal signature, a gesture that belongs only to you, change nothing.

Displayed Originality

Even the corporate world has integrated these elements of positive psychology, the idea of valuing the extraordinary. Overcoming personal handicaps is encouraged. This ranges from the founder of Doctolib explaining on France Inter's airwaves that his stuttering helped him be kind and work hard to stay in touch with others, to companies like the eyewear giant Atol or LinkedIn France taking a stance on dyslexia. The author of the wrong shoe theory speaks of intention, of choice, which would suggest a revival of free will, a reaffirmation. But this idea must be placed in an era that some call the tyranny of appearance.

Psychotherapist Muriel Mazet uses the image of a gallery of costumes that we wear in the social game and that would divert us from our true nature. 'To conform to society, we put on several costumes, but they are sometimes like disguises that take us away from the person we are. One must be careful, she adds, of the trap of the other's gaze, which judges and can be destructive. In the past, we combined being and having, today, we are in the being or appearing, or even in having and appearing.' A vast contemporary literature questions this issue of being oneself. From the philosophical work of Claude Romano titled 'Being Oneself', to the book by psychologist Inès Weber 'Being Oneself', which echoes it. What then emerges is a relationship to self-confidence, to the ability to keep distance and to search for oneself beyond appearances.

From Systematism to Caricature

Beware, therefore, of the syndrome of the biter bitten. If the wrong shoe theory introduces the idea of mischief, comes to ruffle the smooth and abstract oneself from the sartorial injunctions that the women's press of the 1990s summarized in do and don't, it should not itself become a mania. 'One must not overplay, one must be careful not to fall into disguise: the red scarf of journalist Christophe Barbier, the spider of mathematician Cédric Villani.' Gaspard Gantzer, in his advisory strategies, believes more in the singularity of a voice. 'Politicians tend to all speak in the same way, whereas one can in a voice that rises and falls, in a laugh that escapes, mark one's difference.' This aligns with François Armanet's idea that 'as soon as taste is standardized, it becomes bland.' He cites the example of painter Salvador Dalí to show the risk of slipping from detail to caricature: 'From a surrealist invention, his mustache had become a real advertising argument.'

Recommended

Selma Benomar 2026 Caftan Collection: Moroccan Heritage Meets Global Fashion in Paris this Ramadan

25-February-2026

Razane Jammal Wears Zuhair Murad Couture to the 2026 Bafta Film Awards

23-February-2026

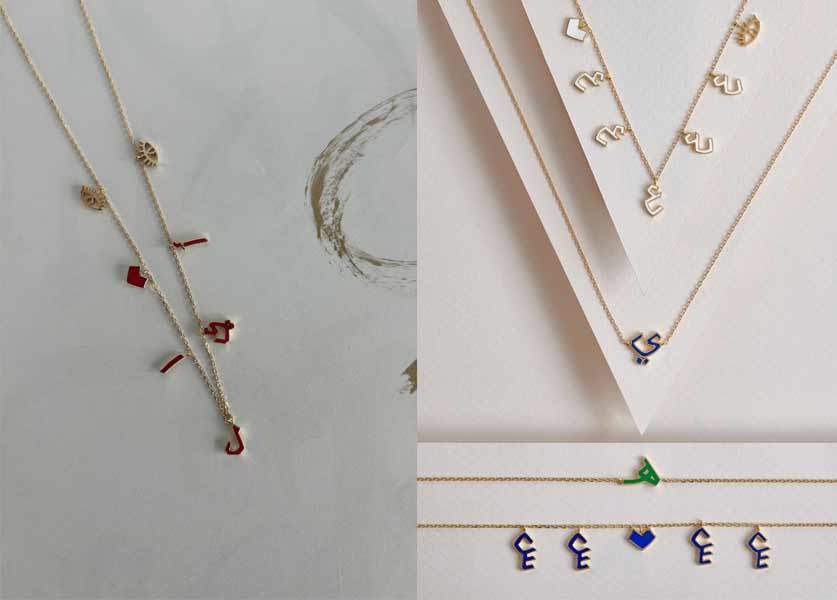

“Inspired by Beirut, Created for the World” Bilal El Dana Celebrates a Grand Opening in Beirut

19-February-2026

Most read

-

1

How to Style Your UGGs Like a Celebrity

-

2

“MAJESTY”: Ziad Nakad’s Spring–Summer 2026 Haute Couture collection At Château de Vaux-le-Vicomte

-

3

Elie Saab Haute Couture Spring/Summer 2026

-

4

Dressed in Chanel, Margot Robbie and Jacob Elordi Light up Paris Premiere of Wuthering Heights

-

5

Gigi Hadid Opens Ralph Lauren Fall/Winter 2026 Show